ctut

This is a C tutorial for those interested in learning about the language. It's

made assuming you only have very minimal knowledge on programming in other

languages. That is, if you already know the basics like what a variable is, and

what if does, this shouldn't be too difficult for you.

The only things excluded from this guide is a complete list of functions that C contains, as there are other sites that are specifically for that.

For contact, please send all mail to suwa★usamimi.info (replace ★ with @.) if

you felt this guide helped, feel free to support

(^^)

Update log

- 2025.12.20: edited function pointer section

- 2025.12.08: slight proofreads everywhere, text editor section updated

- 2025.12.07: extra style section,updated bitwise operator tables to look nicer.

- 2025.12.06: """""small""""" visual tweaks.

- 2025.12.05: bitwise section sign bit noting. this section's huge... also, pointer section updated to be clearer

- 2025.12.04: bitwise section slight additions, added some slop to EX chapter introduction, also changed all makefiles... tell me if anything breaks (^^;)

- 2025.12.03: removing uses of

stdbool.h, as it's no longer needed, array section has multidimensional arrays added, EX chapter introduction added - 2025.12.02: slight boolean section revise

- 2025.12.01: new makefile section, use

%zumore if needed. also fixed entire file in the custom file format section disappearing for some reason?? bitwise section much more elaborated upon. - 2025.11.30: made everything forward slashes, terminal section changes, additional section on casting

- 2025.11.29: lots of revisions, more specifics on printf, pointers w/ arrays section redo

- 2025.11.28: added more information on strings, improved struct chapter, first "public" release

- 2025.11.27: computer chapter

- 2025.11.26: dividing the .pft program, section on writing your own lib

- 2025.11.25: an extra chapter.

- 2025.11.24: a million font changes (sorry to those who liked the old one more)

- 2025.11.23: finishing up library chapter, everything should use C23, new section on custom binary file formats

- 2025.11.22: added preview images for the various text editors, function section redo

- 2025.11.21: corrections on everything, added note on

#pragma once, added note onauto. - 2025.05.13: added chapter on function pointers.

- 2025.05.11: added visualization for linking in chapter 15.

- 2025.05.07: added file I/O section, new section on

main(), and ternary operator section. - 2025.05.06: updated links, added memory allocation section.

- 2024.11.29: Initial version.

Contents

- Resources?

- 0: C

- 1: Computer

- 2: Package manager

- 3: Installing the tools

- 4: Making your first program

- 5: Bare Basics

- 6: Preprocessor

- 7: Data Types

- 8: Arithemetic

- 9: Functions

- 10: Pointers

- 11: Structs

- 12: Enums

- 13: Control flow

- 14: Unions

- 15: Compiling with multiple source files

- 16: Memory Allocation

- 17: File I/O

- 18: A brief on

main() - 19: Function pointers

- 20: Libraries

- EX00: What? That was it?

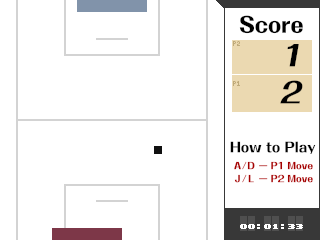

- EX01: A basic game

- EX02: Style

Resources?

Other links you may want to read alongside this.

- The GNU C Manual. It's a bit lengthy, though there's a lot of things that you'll only find there. I'd suggest taking some time to visit and ctrl-f if you want to know more about a topic discussed in one of this guide's chapters.

- cppreference.com. The reference you should be using for finding out the usage of C functions.

- learnxinyminutes.com. A website that has single-page references on a large amount of programming languages. C is just one of them, so if you want a quick reference on other languages as well, you might wanna take a look. Very Useful if you want a short reminder.

- Modern C. A book covering using C in a modern context. Many other books on C tend to be rather outdated (like K&R, another book that often appears in C discussion) so this is one I'd strongly recommend. If you can find a PDF of it, use it!

If you can, try to avoid the similar-sounding website cplusplus.com when

searching for reference on C. cppreference.com simply gives better

information.

Also, don't use video tutorials! They're the absolute worst possible way to learn anything related to programming, despite how tempting it sounds to just be able to sit back and expect to be a professional C programmer after watching one video. Stick to text-based tutorials, they'll be far more informative and easier to learn from. Your first instinct when learning anything related to programming should never be to open up youtube, but to look on a normal search engine for the most informative answer to the issue you're having. Either that, or just read a book (>.<).

0: C?

C's a lower-level language. It's well-suited for embedded use; that is, times where

the user'd want to easily access their own hardware directly.

You wouldn't use it in areas like developing websites and such, but for

programming games? Working on microchips, computer drivers, anything that

requires both performance and low requirements? C's your go-to.

How'd we get here?

A majority of my experience revolves around game programming, so I'll start from there. Around the 80s, most games where written in Assembly: a family of languages that's unique for each type of CPU. For instance, the code found in a SNES game would look and behave very different from one in a Genesis title due to the systems using completely different CPUs, unlike today, where they'd be written in the exact same language. You can probably imagine how annoying it was to port a game from one system to the other, if all your code was in assembly.

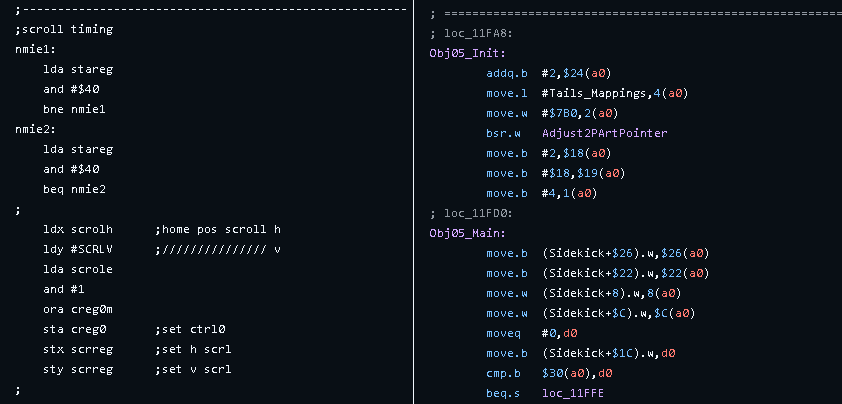

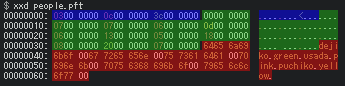

two snippets of code: assembly from Ninja Hattori-kun (Famicom), and assembly from Sonic 2 (Genesis). Both are still assembly, but they're entirely different languages.

Assembly languages of different CPU families are often so different, that it's common for developers to simply emulate games when running them on newer hardware, rather than dedicate an immense amount of time to handwrite code from one language to another. Static recompilation was sometimes even used for certain ports of games (Samurai Shodown on Saturn, Sonic Jam) to get the absolute best performance without resorting to full code rewrites.

Now, with that out of the way, near the middle of the 90s, due to the increasing complexity of games, the question started to then rise among game programmers: Since assembly languages are tied directly to the hardware, how will porting programs to other platforms be dealt with?

Until this point, C wasn't an incredibly popular language among game programmers. Compilers, the software used to translate C into Assembly, weren't very well-optimized, and most CPUs at the time were actually designed with the assumption that the programmer would've wrote their software directly in assembly. It wasn't until the 32-bit era that C started to suddenly become a top choice.

When Sony and Sega sent off their newest systems to developers, not only did

they send off the usual 700-page hardware manuals and CDs full of sample

programs, but they also sent in tooling in C, a first for the time. This was

the start of a new era: developers could write the majority of their game in C

and have it work for multiple platforms with few problems, save for a few

system-dependent topics like rendering. A good call, too; have you seen how

complex game consoles started to get from 1994 onwards?

In the span of just two console generations, writing your entire game in

assembly transitioned from being the norm into something near-unheard of.

Releasing all of your system's tooling in C became the standard for hardware

manufacturers from this point onwards, and assembly had started to lose it's

use, aside from highly-specialized areas.

What about C++?

Before I go into it, let me first say that C is not C++! Two different languages, just with a shared history. With that, C++ was originally a simple extension; C, but with the extra feature of having classes (aka, structs with more functionality), a move that popularized a style of programming known as object-oriented programming. While C's (mostly) stayed relatively the same in the past 20 years aside from a lot of quality-of-life changes, C++'s been getting constant changes to match today's expectations for programming languages (to the point where some say there's too many changes). Surprisingly, C++ actually took a while to gain widespread use, especially in games. It wasn't until the 2000s that it started to get used very often, leading to C starting to take a backseat in popularity, a bit similar to how assembly lost some of it's luster. However, C's always still kept a large market share, most notably in operating systems, such as Linux, along with those in other embedded platforms such as game consoles.

Learning C instead of something like C++ or Python in this day and age may sound like an idea akin to learning latin, though i'd say it's more like learning the alphabet. Ideas from it'll carry on to any other language you use, plus it'll make learning C++ a no-brainer.

0.1: Me?

I feel as though if you're reading this guide, chances are you're not sure how you should really go about it. It's a hard question for me to answer as well, too, though the least I could do is at least explain what I did when i was first learning as a teen. Around nine or so years ago, I was pretty much trying everything possible when it came to game development. Picked up unity, wasn't very fun. Tried Unreal Engine, and since it required a supercomputer for a 13 year old suwa at the time, I quit it not too long after. Did a bunch of miscellaneous open-source projects like pico-8, tic-80, love2d (which i actually kind of liked), though none of them really stuck. Eventually, after a bunch of back and forth between a thousand engines, I came down to the question: how were games (specifically, the games that I liked to play) actually programmed?

Rather than deciding to jump straight into something huge like unreal, I decided to take things in an easygoing way, and simply learn how to program in C, since it seemed to be the most popular language among all of the games I had come across. I downloaded a compiler, and played around with whatever sounded interesting to make. A majority of the programs I had written as a teen weren't even actual "games" either, just components of them, as if I was preparing for something. Some days I would decide to see how a matching puzzle game's algorithm would work. Other days I would see how something like a shmup deals with adding & removing lots of objects. Maybe even something more mundane, like just seeing how to create .bmp files. Even though I wasn't really making anything major, I didn't actually hate doing it or even really get bored of it at all. It was kind of the same mindset I have when doing something like playing a puzzle game like tetris or panel de pon or picross or whatever endlessly.

I think a major turning point was when I eventually started to branch out and make programs with various C libraries that I found, like using SDL to make small game engines (something this tutorial does actually cover later on!), or playing around with homebrew development libraries to make games in C for game consoles. At first, making games kind of felt aimless, though it got significantly easier after I made a switch to programming with no plan to always writing a design document before I make any game project. Eventually, I decided to learn C++ as well, as it made certain tasks like writing tools for my games a lot easier than if I were to use C alone. Fast forward a few years, and now you're with me right now. When I recall how I tried to learn things like composing music or drawing illustrations, it was a real pain in the ass, though somehow something like learning C actually tended to be the easiest out of all of them. Which is kind of strange to think about from an outsider's point of view, as it has that reputation of being the exact opposite of what a beginner would want to learn, even though i'd say it should be their first choice.

Though I was pretty familiar with C, I learned a lot of the other programmers around my age had no experience at all with it. Even worse, I couldn't really give them much good reference material to work with to learn the language. Have you ever tried giving something like K&R to a 19 year old? Even worse, Windows provides a horrible environment for programming, as there's quite a bit of steps that have to be done just to compile a single program. Altogether, it's like feeding a baby a ghost pepper. So, I spent a week or so writing the initial draft of this document, as a plain .txt file; a C tutorial, without any of the useless bits. Not only would it be about the language, but describing how to navigate your development environment efficiently as well, as I noticed it's a thing a lot of tutorials tend to lack. Now, after exactly one year of writing, it's finally in a state where I'm actually having trouble finding topics that I haven't already covered. I hope you get something out of this... if you've made something cool, don't hesitate to mail it and show me!

1: Computer

In order to use program effectively, you must also know how to use your computer effectively. Many people who use a computer often seem to assume that also means they know how to use it well, but that is not the case. If you plan on programming, you can't just be lazing around and typing at a rate of two words an hour! By using your computer well, I mean:

- Knowing how to edit text, and how to edit it fast. Yes, this means learning

more hotkeys than

ctrl-s,ctrl-c/v, andctrl-z/y. Going out of your way to shorten repetitive tasks that can be cut down to just a single hotkey is a very useful skill. - Navigating a terminal. Not knowing how to use a terminal will be an extreme disadvantage, so the next section will be teaching exactly that.

- Having intuition. This tutorial won't tell you every minor thing about a computer, so you're expected to still use your head and think about why you're doing whatever you're doing. A general tip I give to new programmers is to make sure you understand every line of code that you're writing thoroughly. I've seen so many newbies try and fail repeatedly at learning programming, only for me to find out that they haven't googled any part of what they're actually writing.

- Understanding your errors. Please, if you get an error when running a program, do not just stare at it dumbfounded! Read the error very carefully, and google the error if you still can't resolve it. Retrace your steps to the point where the code started erroring, if it's needed.

1.1: Using a terminal

This tutorial is written with a terminal in mind. You're going to be using it to do pretty much everything, from compiling, to running programs, or even writing code (if you're using a terminal text editor, like Vim). Though, I know many people who are learning C for the first time won't have much experience with a terminal, so I've written a brief cheat sheet you can use. Please do not hesitate to refer to it often when programming.

※*Note: <parameter> means said parameter is required. (parameter) means

said parameter is optional. For example, dir (path) does not mean that you

type dir (C:/Users/suwa), it just means that you can either use dir or dir C:/Users/suwa. This also goes for documentation and explanation of other

things in this page as well. Also, some of these commands will only be

available after you have installed a package manager.

win+R-> typecmd.exe-> pressenter: Starts windows' terminal.win+R-> typecmd.exe-> pressctrl+shift+enter: start windows' terminal as adminYou can also use

win+Xthen selectCommand Promptto start cmd.exe, though I prefer thewin+Rmethod.cd (path): sets the Current Directory to the specified path, for example,cd C:/Users/suwa.mkdir <directory>to create said directory. Alternatively, you can usemkdir "<directory>". This alternate syntax can fix an issue in Windows where mkdir errors if you use/instead of\.ls (path): lists all the files in the specified path. You can omit thepathentirely to list all the files in your current directory.ls -amay be used to additionally reveal folders marked as hidden.rm <filenames>: Deletes file(s).rm -rmay be used to delete a directory.where <pattern>: Shows a list of where files with the given pattern are located. (ex.where notepad.exe). Useful for if you want to know where a certain executable/DLL is.The

Uparrow key will change your text to the last command you wrote.Likewise, the

Downarrow key will do the same but to the one after.Page Downwill change your text to the latest command.Tabcan be used to autocomplete when writing paths (..usually.)ctrl+ccan be used to exit out of most command-line programs.

Useful notes:

.is a special path: it's always the current directory...is another special path: it'll always be the parent directory. If you wanted to navigate to the parent directory, you'd docd ... This can be mixed with other paths, for example,cd c:\users\suwa\..would enterc:\users.Just about every command has a help menu you can view by entering

<command> --help. Note that for commands that came with Windows, it'll be<command> /?instead. Why? Difference in standards between Unix and Windows programmers.Arguments that have spaces can be used, if you surround them in quotes. For example,

mkdir Project Folderwould incorrectly create the foldersProjectandFolder, whilemkdir "Project Folder"would actually create the folderProject Folder.Commands can be chained with

&&; this operator makes it so the second command executes if the first one executes successfully. Example:cd c:\users && lswould enter the directoryc:\users, and thenlswould list all the files inside of it.To run an executable from the terminal:

- In windows, you simply type it's path: for example,

program.exe. The.exeis actually optional! You're free to omit typing it, and just doprograminstead.- You can run a command in a separate command window by prepending it with

start. (ex.start ls && pause)

- You can run a command in a separate command window by prepending it with

- In linux, it's the same, except if it's a relative directory, you must use

./. For example, if the program is in your current folder, you must use./programinstead ofprogram. Also, note that executables in Linux don't need a file extension like.exe.

- In windows, you simply type it's path: for example,

For linux:

- Directories should be using

\(backslash) instead of/(forwardslash), unlike Windows where it tends to prefer\, so edit your commands and files accordingly.

You'll be using all of the above as you program, so don't forget a single bit

of it. If you have the ability to shorten your commands via &&, do it.

Don't retype commands you've already typed out either, just use the arrow

keys and pgup/pgdown to automatically paste the previously-typed command.

1.2: Text editing

General text-editing tips:

-

F2in many programs renames a file and/or an item. Yes, even in windows explorer. You would be very surprised to see how few people know you can do this! -

ctrl-left/rightin a lot of software shifts your cursor to the next or previous word. -

shift-left/rightin a lot of software can be used to manually select text. It usually can be combined withctrl-left/rightto select words faster. - Obviously, use

ctrl-sto save,ctrl-ato select all text,ctrl-c/ctrl-vto copy and paste. - In many programming-oriented text editors, there's a hotkey to indent your

selection by one level. Usually, it just involves selecting text and

pressing

tab(orshift-tab, to move the text backwards).

2: Installing the package manager

Note: If you're on linux, there's a 99% chance you already have a package

manager installed. In that case, simply install the gcc, clang, and

binutils packages using your package manager, and skip all of

this. This also means that you can omit the

mingw-w64-ucrt-x86_64- bit of each package name whenever this guide mentions

installing a package.

The longest but also the easiest step. To install the C compiler, you need to first install a package manager. It's a command-line tool that deals with installing and updating all your tools and compilers for you, so you don't have to manually download them yourself. You could kind of think of it like an app store.

2.1: Setting up msys

NOTE: Make sure all of the paths and filenames you use for your projects don't contain any spaces or unusual characters. They can and will make certain tools break when used. If you really want to use a space that badly, use an underscore.

- Get msys's installer from https://www.msys2.org/, under the

Installationsection. Install it somewhere nice and easy to recall, for example,C:\compa\msys64, instead of something stupid like a Downloads folder. - Follow the first four steps they have listed, as the rest is optional. Doing the rest of the steps won't break anything, though, it'll just make things take a few minutes longer.

After this, you now have msys installed, along with its package manager, pacman.

2.2: Setting up your PATH

After following the above steps, you now have a package manager installed,

but windows doesn't know where to search for it! If you were to type the

line pacman --version in your terminal right now, it'd show an error, but

c:\compa\msys64\usr\bin\pacman.exe --version wouldn't (assuming msys64 was

installed in a folder you made called c:\compa).

This'll bring problems down the line once your compilers are installed, too;

windows won't know where to search for them, either.

To handle this, you must add msys's folders to your PATH. If you've ever

tried running notepad.exe in your terminal right now, you would've noticed

that it ran the program without any problems, Though, how does Windows do it?

How does it search through every possible folder on your PC to know where

notepad.exe is? The answer is that it doesn't. It simply searches through

a short list of folders Windows contains, called your PATH, to see if it's

there.

However, the issue with the above is that adding msys' folders to your PATH adds all of the binaries and libraries of msys to it... which hasn't actually ever been a downside in my case, personally, as all of msys's software have just been plain better than any Windows counterpart. Though, if you really dislike using msys' tools, you've got two options:

- Proceed with the rest of this section, adding msys to your PATH, allowing you to use any program from msys anywhere freely.

- Don't edit your PATH at all, and instead skip directly to the next

section. ⚠️ This means that whenever you want to use pacman,

along with any other software in msys's folder, you need to always use the

ucrt64.exeprogram in msys's root folder, instead of your normal terminal. Note that the terminal there defaults to bash, so typecmdafter opening the program if you wish to switch back to windows'cmd.

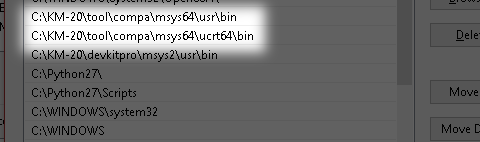

Now as I was saying, to view your PATH and to add msys to it:

- Search for

Edit the system environment variablesin windows' search, and open the program. - Select

Environment Variables... - Go to the

System variablessection and scroll until you reach a variable titledPath, then selectEdit. - Select

New, and add the two folders:<directory of msys>\usr\bin<directory of msys>\ucrt64\bin

- Move the folders upwards so that they're above C:\Windows\system32. This'll solve a conflict that may happen later.

- Select

OKto everything and close all of the above windows that you just opened: closing them applies your changes. - Close and reopen any terminals you have up. You'll have to do this each time your PATH is altered, otherwise changes to your PATH won't be recognized!

For an example, my PATH is setup like the above. For my case, I don't like to

just stick everything directly in C:\, so I installed it to a folder I made

called C:\compa, along with all my other compiler-related tools. Note how

the two directories are above C:\WINDOWS\SYSTEM32! You can ignore the other

folders.

If you've done the above steps, run pacman --version in one of your

newly-opened terminals. If it ran without any problems, that means you're done

installing your package manager.

3: Installing the tools

The second easiest part. It'll all be done via your package manager.

There's two main sets of C/C++ compilers that get widely used: gcc/g++ and clang/clang++.

-

gccis GNU's C compiler. It's old and most widely-used one. Installing it also gives youg++, the C++ compiler. -

clangis a newer C compiler. It's a tad faster, and it's error messages tend to be more helpful than gcc. Installing it also installsclang++, the C++ compiler.

Just to be sure, both will be installed. You'll also be installing binutils, which is a set of tools you'll also probably be using alongside your compiler.

pacman -S <package_names> can be used to install a package (or several, at a

time). So, install gcc, clang, and binutils by running the following

commands:

pacman -S mingw-w64-ucrt-x86_64-clang

pacman -S mingw-w64-ucrt-x86_64-gcc

pacman -S mingw-w64-ucrt-x86_64-binutils

If you get any warning saying you already have a package, it's fine to download

it anyway. Once they've all been installed, test your compiler out by running

clang -v to view clang's version. If it shows, then you can finally get to

programming.

I would strongly recommend eying MSYS2's website often, as it has a list of all packages you can download, along with each page showing a command you can copy to download each package. Lua, python, SDL and such can be found there. If you plan on learning other languages, I'd suggest installing them this way if you can, rather than downloading from their respective websites.

3.1: "ucrt"?

Oh, by the way, if you were wondering what the hell is up with the

mingw-w64-ucrt-x86_64- nonsense, I can give a brief explanation.

-

mingw-w64, or Minimalist GNU for 64-Bit Windows, is exactly what it says on the tin: the same tools made by GNU that Linux users would normally have installed on their computers, but ported to Windows. -

ucrt-x86_64means that a package uses msys2's UCRT64 environment, which uses Microsoft's Universal C Runtime. When you run a program, a set of startup code called a C Runtime (or CRT for short) is ran before any of the code you wrote gets executed. There's a ton of different runtimes, and UCRT is just one of them.

msys2 has many different environments, for specific needs: some users don't

need anyone who doesn't already have msys2 installed to run their programs,

other users need their programs to be 32-bit, and some users prefer their

programs to have been made by a specific compiler. For the sake of this

tutorial, we'll be using the environment that's the easiest to use, UCRT64.

This is also why I had you use <directory of pacman>\ucrt64\bin when you

added msys2's folders to your PATH.

4: Making your first program

4.1: Text editors

You're going to need one if you plan on writing any programs, even the simplest applications, so decide on one now. Specifically, one designed for writing code. A lot of you probably already know by now, but software such as google docs or MS Word are out of the question when it comes to writing code, as they're meant for writing literature and books rather than being general-purpose. However, it'd be stupid of me to assume everyone knows of every text editor in the world, so i've compiled a list of editors for you to choose from, along with a few to avoid as well.

Just about all of these also support plugins, so you can add features like autocomplete, syntax highlighting, and the like, so I encourage you to find a few you might like.

Not recommended

Notepad

- One undo step, no syntax highlighting, only one file can be opened.

- Don't use it if you're not stupid.

Visual Studio

- Don't confuse it with it's similarly-named cousin, Visual Studio Code! They're entirely different.

- An IDE. In other words, it's a text editor that can also compile/debug code.

- ""free"", as in, certain versions need a license.

- Heavy on resources.

- Generally, a pain in the ass to use with. It's compiler comes with it's own set of things to keep in mind, some of which are grossly outdated, and as such it won't be recommended for this guide. Don't use it unless the company you work at is forcing you.

Recommended

Notepad++

- Notepad but good.

- Very light on resources.

- No true downsides... besides looking kinda ugly sometimes.

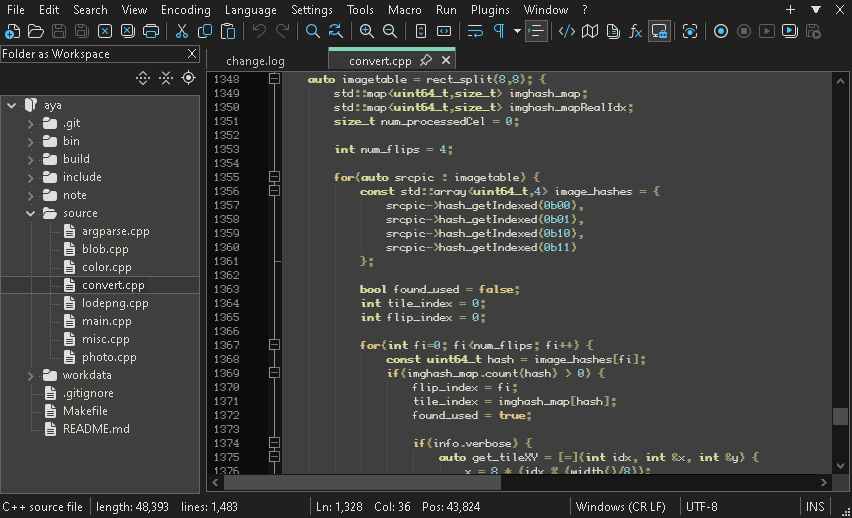

Visual Studio Code

- Note: i'd strongly recommend using VSCodium instead of regular VSCode. Same exact editor, but with all the AI slop and tracking from Microsoft removed.

- Unlike visual studio, it's a normal text editor. It's also free, unlike visual studio.

- There's a quadrillion plugins available to use with it.

- Chromium-based, so it tends to hog resources much more than other editors.

- Has a few things to note:

- To start programming, you'll want to open the folder of your project via the

Filemenu, rather than just opening one single file. - It has a builtin terminal, though this tutorial is made assuming you are not going to be using it.

- To start programming, you'll want to open the folder of your project via the

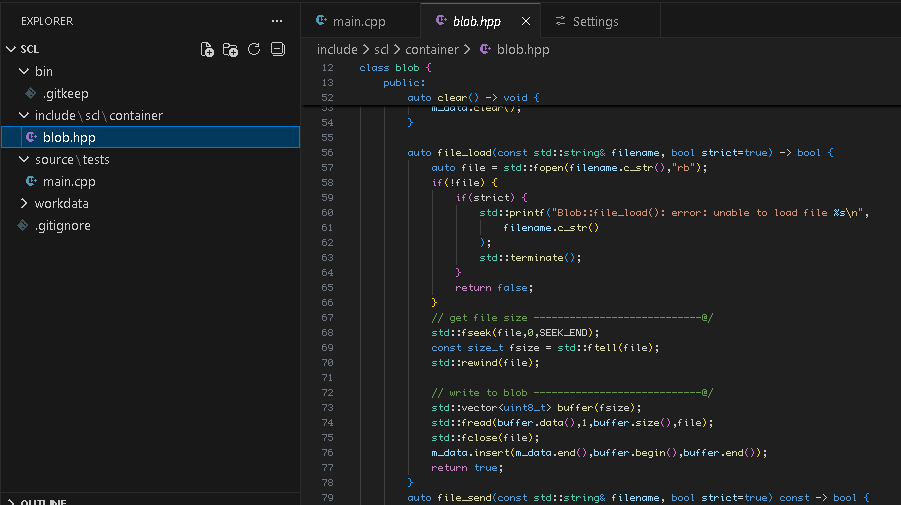

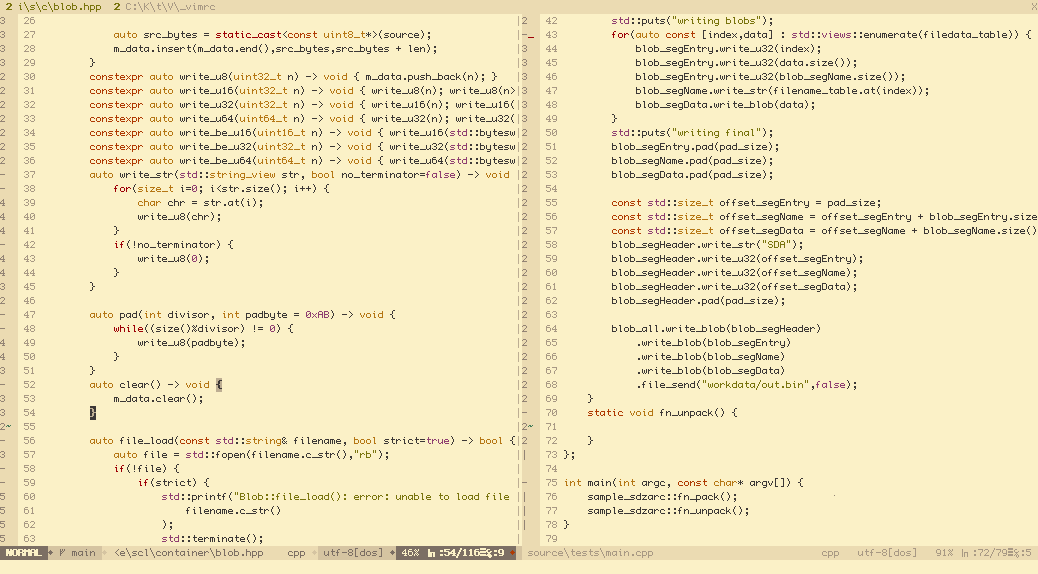

Vim

- Designed to be operated using only your keyboard. (though, you may still use your mouse if you want)

- Highest performance and customization of all the editors listed here, uses an incredibly light of resources.

- Slight difficulty curve, it'll take a few days before you're familiar with it.

- Plugin manager isn't builtin, but you can download one here pretty easily.

- Comes with two versions: one that runs in a separate window (called GVim), and one that runs in your terminal. (just called Vim). The one in the image below is my current configuration with GVim, if you were wondering.

Sublime Text, Sakura editor, other similar programs

- Does just about the same as notepad++.

- Use it if you want a different look, i guess.

Emacs

- You could try it if you wanted to, but I wouldn't be able to help you...

In short, use VSC if you own a gaming computer, Notepad++ if not, or Vim if you can type fast. I personally use GVim, since it's extremely flexible, lightweight, and looks pretty nice.

4.2: Basic folder structure

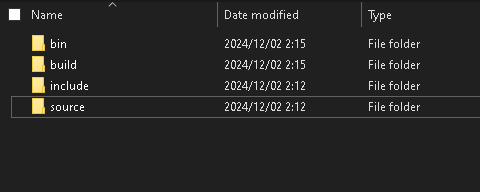

You can't just place a bunch of C files inside a folder haphazardly, otherwise your programs will be an unreadable mess to both you and your peers. I'd recommend that any C programming project for now should have at least the following folder structure:

- Project root

source/: Where your source (.c, .cpp) files will be.include/: The header (.h,.hpp) files that you write.build/: Should hold intermediate (.o) files.bin/: Holds the final executable(s) (.exe) of your program.

4.3: A single-file C program

Create a folder for your first project, and then give it the folder structure

as described above. Then, navigate to your project's root folder via

your terminal. Use cd to get there, if you don't know how.

Create a file source/main.c. The text will be the following:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

puts("hello world");

return 0;

}

To build your program, run:

clang --std=c23 source/main.c -c -o build/main.o

clang build/main.o -o bin/program.exe

This will result in the executable bin/program.exe being compiled. In

programming, a compiled executable is also interchangeably known as a

binary... don't confuse it with the numeral system, though!

Now, to actually run your program, it's simple. Just like how was

described earlier, in Windows you can either type bin\program.exe, in

your terminal, or type bin\program. In linux, it's just ./bin/program.exe

(Though, note that in linux, most users tend to make their executables not have

any file extension.) Since this is a command-line program, you should run it

from your terminal, as if you were to try and simply click the .exe file,

you'd be met with a window that starts up and immediately closes!

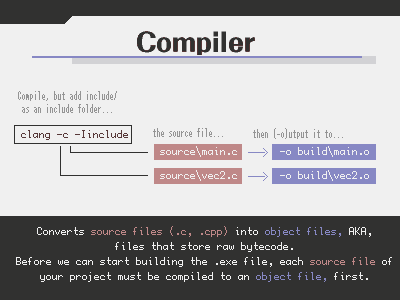

4.4: "okay, but what is the compiler doing"

As you already know, your CPU does not execute .C files, or any text file, for

that matter. It only operates on bytecode, aka, data that consists entirely of

bytes, for example 0x01 0x04 0xF3 0xFC.

To create said bytecode, you must first compile a .C file into an object file;

a file that stores the bytecode of a .C program.

clang --std=c23 source/main.c -c -o build/main.o

The above uses the -c flag to signal that clang should compile into an object

file, then uses -o <output> to output said compilation into the object file

build/main.o. Also, since this guide will only be using the latest

version of C, C23, we add --std=c23 to our flags. Your compiler actually

defaults to a slightly older version of C, so explicitly setting the version

has to be done.

Though, the thing about this compilation is that even though it compiled our

.c file to an object file, object files are not executables. They're just

raw, compiled code, and your PC isn't going to know what to do with it. It's

like if you had all the parts required to build a computer, except they're all

disassembled and stored in boxes. Because of this, a final, additional step is

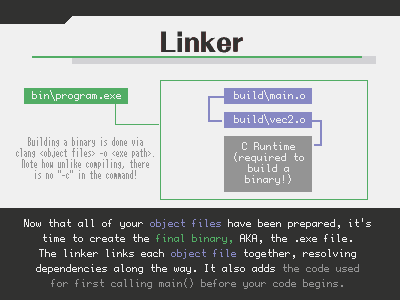

required to create the actual executable:

clang build/main.o -o bin/program.exe

This uses a component of your compiler called the linker to link your

newly-created object file(s) into a single binary, and -output said binary to

the path you specified (bin/program.exe). Linking our binary like this also

automatically adds the C runtime to it as well.

So, writing any C program will always involve the following:

- compiling your source into object files

- linking your object files into an executable.

Compile, link. It's important to know both of these distinct steps, as there'll be countless times where some of your errors are from your compiler while others are linker errors.

4.5 "okay, but what is the code doing"

I'll go over it line-by-line.

#include <stdio.h>

#include is not a function, but what's known as a preprocessor directive.

In this case, this line is for including one of C's builtin files stdio.h

into your file, which includes the standard input/output

functions for use with your code, such as puts(). You'll need it if you want

to output any text back to your terminal (like the hello world! text), or

interact with files. It's required to include this to use the printf() and

puts() functions.

int main() {

}

Every C/C++ program needs a function titled main(). It's what gets executed

when your program starts, so you'll be greeted with a nice error if you try

to link a program without it. These lines define the function main().

puts("hello world");

Calls one of C's builtin functions puts(), which outputs the string (a

sequence of characters)

to the terminal.

return 0;

Every C program also returns a number to the OS signalling how the process

ended. If the process ended safely, a 0 is returned. On error, -1. Other

values depend on the system. This number's referred to as an exit status. Since

main() is a function that returns an int (hence the line int main()), the

exit code of your program is whatever it returns. If this sounds confusing,

don't worry! It's impossible to demonstrate a C program without also

demonstrating main(), so I had to explaining it now. You'll learn more about

it as you read.

Also, one thing you have probably noticed by now is that each statement

ends with a semicolon (;). This is required to do, unlike a lot of recent

programming languages today. If you want an easy reminder of what lines to put

semicolons on and which lines to NOT put them on, note that that certain lines

(like the curly braces (}) at the ends of function definitions, or the

#include lines) are not statements, so they do not need semicolons after

them.

There's quite a bit of things to explain with a minimal hello world! program

in C compared to other languages, though they're all things that are required

to know, so I'd say to not worry too much about it for now if you don't

immediately understand.

4.6: introduction to printing

puts() is only for printing strings and nothing more. For printing variables,

printf() will be used.

It's syntax is a bit different:

printf("hello world\n");

the \n at the end of the string is a control character; specifically, the

newline character. It denotes that the terminal should shift it's cursor to the

line below, as if you had just pressed Enter on your keyboard.

Omitting it will result in the cursor not moving at all. To demonstrate, try

copying the following inside your main() function. Though, be sure to NOT

remove the return 0; line at the very end of the function! Your main()

still has to return, no matter what you do.

printf("hello");

printf("world");

printf("!");

Rather than getting:

hello

world

!

you'll see:

helloworld!

puts() on the other hand will always insert a newline character after

whatever you print. This is only just one of the differences between the two

functions, though.

5: bare basics

5.1: Comments

// comments that look like this span a single line.

/* On the other hand, if you really need to be writing longer blocks of notes,

multi-line comments can be written like this. */

I'd suggest you get used to writing comments for all of your code. Something common i've seen with newer programmers is to either not comment at all, or only comment if they have to do it for a school assignment. Don't be stupid, just write them. not only for other people, but so your own code is readable by you.

Though, that doesn't mean to comment over each and every individual line. For me, I usually just comment notes above chunks of code, only doing detailed comments if it's a hard-to-read portion for someone reading it for the first time.

5.2: Variables

To declare something is to make it known. To define something is to assign it's data to value. This is also sometimes referred to as assignment. To create a variable, you can either declare and define it, or just declare it.

// to declare a variable, write it's type, then the name.

int number1;

// you can then later assign the variable to whatever you want.

number1 = 4;

// variables can be defined and declared in the same line.

int number2 = 7;

Declaring a variable without defining it will result in the variable staying uninitialized. Since it's uninitialized, it'll have a garbage, unknown value. In C, variables do not get automatically get assigned a default value. You should always initialize your variables to something so you don't end up mistakenly using uninitialized data.

Note that after a variable's declared, you don't have to define it's type again. Attempting to do so would result in an error.

// why are you setting number's type twice in a row? this would error!

int number = 3;

int number = 7;

// OK, this would set number to 3, then re-assign it as 7.

int number = 3;

number = 7;

Variables are local only to the block they were declared in. Thus, you can't access variables from a different scope.

int main() {

int number1 = 4;

// note: curly braces on their own can be used to create a new scope.

{

int number2 = number1 + 2;

}

int number3 = number1 + number2; // error! number2 is in a diferent scope.

}

Variables with a value that never changes are referred to as constants. It's

denoted by a const preceding the variable's name & type.

const int MAX_VALUE = 40;

MAX_VALUE = 3; // this line would error! you can't modify a constant.

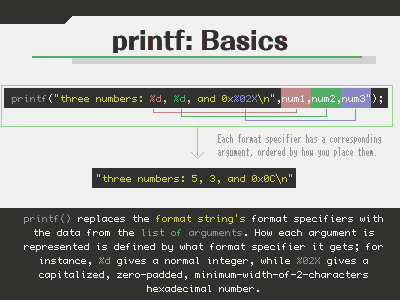

5.3: Printing variables

In order to print numbers to the terminal, puts() can't be used, as it's only

for strings. To do so, we need to use its more flexible alternative, printf()

(short for print formatted). printf is a rather unique function, as its one

of the few builtin C functions to support variadic arguments; in other

words, you can pass a varying number of things to it, instead of only

being able to print one single variable at a time.

As for using printf, if you read the earlier chapter, you would've

probably been confused as to how you'd use it effectively compared to puts().

The answer is simple. Using printf means you have to pass two main things: a

format, which describes the layout and what kind of data each argument will

be interpreted as, and the arguments themselves. For example:

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

// Our variables that we will be printing.

int num1 = 5;

int num2 = 3;

int num3 = 12;

printf(

"three numbers: %d, %d, and 0x%02X\n",

num1,num2,num3

);

return 0;

}

would print:

three numbers: 5, 3, and 0x0C

Again, note that printf does not automatically insert a newline, so \n must

be added to the end of the format. Now, how does printf's format work? It's

just a string, though with a few interesting things:

"three numbers: %d, %d, and 0x%02X\n"

%d is what's called a format specifier. They all start with %, followed

by more characters for additional options. There's many different types you can

use for each format specifier, but %d is used to denote that the text at that

point should be replaced the current argument, but as a signed integer, with

decimal representation. (Note that I'm using the second definition of the term

decimal, which refers to numbers that use 0-9, and not a decimal point.)

After each format specifier is processed, printf then proceeds to the next

argument in its list of arguments. So, the first %d will be replaced with

num1, the second %d will be replaced with num2, and the third will be

replaced with num3, except with an added difference: it uses the %02X

format specifier, which means:

-

0, so empty spaces are filled with zeroes. -

2, so the text will have empty space added until it's2characters long. -

X, so the text will have decimal representation, rather than hexadecimal representation. Since this isXand notx, the text will also be capitalized.

Also, the 0x part isn't actually part of the format specifier at all, it's

just normal text.

For a list of format specifiers, see the documentation for printf.

There's many other functions in the printf family, as well. Another important

thing to add is that the number of arguments must always match the number of format

specifiers. printf is not smart: it will blindly attempt to use more

than its able to use. If you were to attempt to do:

printf("numbers: %d, %d\n",1)

crashes could end up occuring, as a result of the second format specifier having no argument to use.

6: the preprocessor

First thing you may notice in C code are the odd lines that begin with # at the very

start. As explained earlier, your compiler splits the compilation

process into several steps, and preprocessing is one of the earliest ones.

Before any of your code is actually properly compiled, your preprocessor, which

is essentially a very advanced text replacement program, goes through every

line and deals with any #includes, #defines, and so on.

What does that mean in practice, then? First, let's go over another main concept of working with C: header files.

The following two files are include/player.h and source/main.c,

respectively.

#define PLAYER_MAXHEALTH (30)

#define PLAYER_DAMAGEVAL (PLAYER_MAXHEALTH-3)

// a small note: the "extern" keyword is usually used for undefined variables

// that get declared later on in a different file. It's not *needed*, so it's

// usually just there for clarification.

extern int gPlayerHP;

// another note: for #include, <> is usually used for builtin header files. ""

// is the one that's commonly used for user-made headers.

#include <stdio.h>

#include "player.h"

int gPlayerHP = PLAYER_MAXHEALTH;

int main() {

gPlayerHP -= PLAYER_DAMAGEVAL;

printf("player HP: %d\n",gPlayerHP);

return 0;

}

To compile, you must add the path that your include files will be in, as your

compiler has no idea where they could be. The -I<includepath> flag does so.

All it does is add includepath to the list of folders to include files from.

For the sake of this example, we will be adding the include/ folder, hence

-Iinclude.

clang --std=c23 -Iinclude source/main.c -c -o build/main.o

clang build/main.o -o bin/program.exe

Another reminder that you can press the up arrow to select the last command you entered in your terminal...

6.1: Macros

Anyway, i'll go over the two files. First is include/player.h.

It's a file that has two defines, and one global variable, which is used for

holding a player's health.

Using a value from a #define literally copies that text into your code. So,

the following:

#define CONSTVALUE 1337

int number = CONSTVALUE;

would become:

int number = 1337;

These are known as macros.

Macros are used as-is, that is, they just copy it exactly as you wrote. An

easy beginner mistake is to ignore that they do this, for example:

#define DAMAGEVAL 30 - 3

#define DAMAGEMUL 2

int number = DAMAGEVAL * DAMAGEMUL;

Spot the error: what would the value of number be?

If you answered 54, you're wrong. The expression would evaluate to:

int number = 30 - 3 * 2;

In other words, 24.

An easy fix to this is to wrap all of your macros' definitions inside parentheses.

#define DAMAGEVAL (30 - 3)

#define DAMAGEMUL (2)

// number would be 54, as intended

int number = DAMAGEVAL * DAMAGEMUL;

6.2: Including headers

Now, as for #include, it's a basic preprocessor directive that includes a

file into your current file. That is, it preprocesses that file's text,

then includes all of that onto your actual file. So, after preprocessing,

main.cpp would become this:

// <stdio.h is a long file, but imagine it's here...>

#define PLAYER_MAXHEALTH 30

#define PLAYER_DAMAGEVAL PLAYER_MAXHEALTH-3

extern int gPlayerHP;

int gPlayerHP = PLAYER_MAXHEALTH;

int main() {

gPlayerHP -= PLAYER_DAMAGEVAL;

printf("player HP: %d\n",gPlayerHP);

return 0;

}

Yes, #include is just a text copier. Besides preprocessing the text before

it copies, all it does is insert it in your file.

6.3: ifndef

#ifndef PLAYER_H

#define PLAYER_H

// define/enum --------------------------------------------------------------@/

#define PLAYER_MAXHEALTH (30)

#define PLAYER_DAMAGEVAL (PLAYER_MAXHEALTH-3)

// externs ------------------------------------------------------------------@/

extern int gPlayerHP;

#endif

#include <stdio.h>

#include "player.h"

int gPlayerHP = PLAYER_MAXHEALTH;

int main() {

gPlayerHP -= PLAYER_DAMAGEVAL;

printf("player HP: %d\n",gPlayerHP);

return 0;

}

First thing you may have noticed changed about the header file is the

#ifndef, #define, and #endif directives. Structuring a header like this

is referred to as a header guard,

a technique used to make sure a file only gets included once. In this instance,

if player.h is included, then the preprocessor:

- Checks if

PLAYER_Hhasn't been defined (#ifndef PLAYER_H) - If it hasn't...

- We define the symbol

PLAYER_Hvia#define PLAYER_H. Theoretically, this symbol can be named anything, but we usually just name it something similar to the filename. - The rest of the lines get pasted into the current file, until

#endifis reached.

- We define the symbol

- The next lines of text are processed.

C doesn't make any effort to stop you from including the same file multiple times. That is, if you removed those 3 directives, then added the following lines:

#include "player.h"

#include "player.h"

#include "player.h"

#include "player.h"

your preprocessor would simply paste the file four times in a row! Your compiler is none the wiser, therefore it'll error in almost all cases. Re-adding the header guard would make sure the file'll never get re-included.

6.4: pragma once

Surprise! In newer versions of C/C++, header guards can be replaced with a

shorter alternative that accomplishes the same thing, #pragma once. If you're

wondering why i'm telling you this after already telling you about header

guards, it's because you'll often run into both when reading other programmers'

work.

I'd suggest you use this from now on rather than writing header guards, if you

can. Using #pragma once is incredibliy easy: just place it at the top of your

header, and you're done.

#pragma once

// define/enum --------------------------------------------------------------@/

#define PLAYER_MAXHEALTH (30)

#define PLAYER_DAMAGEVAL (PLAYER_MAXHEALTH-3)

// externs ------------------------------------------------------------------@/

extern int gPlayerHP;

7: data types

For a full list of data types, see this page. Try the examples in the next few sections out yourself, by copying them inside your main() function.

7.1: ints, floats

// char: usually an 8-bit integer.

// short: usually a 16-bit integer.

// int: usually a 32-bit integer.

// long long: usually a 64-bit integer.

char num_a = 1;

short num_b = 2;

int num_c = 3;

long long num_d = 4;

// Printing integers is done via the '%d' format.

// Likewise, long long integers require '%lld'.

printf("num_a is %d\n",num_a);

printf("num_b is %d\n",num_b);

printf("num_c is %d\n",num_c);

printf("num_d is %lld\n",num_d);

Integers are self-explanatory: they're whole numbers, so they have no decimal

points. Alongside the basic int type, long, char, and short are also

used, though they don't have much use other than in places where you need to

store data of a specific size, so int tends to be the most commonly used.

The exception to this is char, as text tends to be made up of dozens of chars

in sequence.

I used the word usually, as the size of the above data types actually does depend on what CPU you're compiling for. You might've seen CPUs being referred to as "16-bit", "32-bit", "128-bit", etc. Each CPU actually has a native datatype, AKA, the "word", that they're best-suited to be dealing with. 16-bit CPUs operate with 32-bit data much slower than they do 16-bit data, 32-bit isn't very fast with 64-bit, and so on.

Though, "128-bit" CPUs are more of marketing jargon than anything, as no commercial CPUs are natively 128-bit. The PS2 is advertised as 128-bit, though in reality it just means it's capable of operating on four 32-bit words simultaneously.

unsigned char fullbyte = 254;

unsigned int fullint = 3000000000; // 3 billion!

printf("unsigned byte: %d\n",fullbyte);

printf("unsigned int: %u\n",fullint);

Unsigned numbers, aka, numbers that can't become negative, can also be used

by suffixing whatever type you're using with unsigned. With this, types like

char will go from 0 to 255 rather than -128 to 127. It may seem useless, but

they're often used for numbers where having a negative part wouldn't make any

sense, such as file sizes or data indexes. Also, to use printf with unsigned

integers, the %u format specifier should be used.

float num_e = 5.25f;

double num_f = 3.15;

// A note on printing floats: you can specify how many characters you want

// to print. .12 would print a maximum of 12.

printf("num_e is %f\n",num_e);

printf("num_f is %.12f\n",num_f);

Floating-point numbers, or floats contain a decimal point, unlike integers.

Double-precision floating point numbers, or doubles are the same, except

they're more precise, along with usually being 64-bit in size, as opposed to

floats being 32-bit. By the way, if you're wondering why f is added at the

end of 5.25 in the above example, it's because writing numbers with a decimal

point in C defaults to them being interpreted as doubles, then being

converted to whatever you're doing. So, float num_e = 5.25; would actually be

the double 5.25 being converted to 5.25f, rather than just 5.25f from the

start. In short, use the suffix f for floats, and no suffix for doubles.

If you don't care too much about precision, either because it's not needed or because you are developing for a system where doubles have a performance penalty, it's fine to use floats throughout your entire program instead of doubles, though it's important to keep in mind that they become far less precise the bigger they are.

7.2: conversion

To convert one type to another, the syntax is (newtype)oldvalue. This is

referred to as casting. Expect a loss of precision when converting from a float

type to an integer type, or from a larger integer type into a smaller integer

type. Specifically, for converting a float or a double to an integer, the

entire fractional part is REMOVED, not rounded. That is, (int)(2.9f) would

be 2, not 3.

double num1 = 3.141592653;

int num2 = (int)num1;

float num3 = (float)num1;

// print the two converted numbers

printf("num2: %d\n",num2);

printf("num3: %f\n",num3);

7.3: automatic typing

Want to create a variable that's the same type as another? Use the keyword

auto rather than the name of the type. It'll automatically pick the type

based on whatever you set it's value to.

Note: As of the time of this writing, this is still a very new feature for C,

so you must compile your code with the C23 standard by adding either -std=c23 or -std=gnu23

to your gcc/clang command during compilation.

double num1 = 3.141592653;

int num2 = (int)num1;

auto num1_cpy = num1; // num1_cpy will be of type "double".

auto num2_cpy = num2; // num2_cpy will be of type "int".

// print the two converted numbers

printf("num1_cpy: %f\n",num1_cpy);

printf("num2_cpy: %d\n",num2_cpy);

I would heavily advise against using this for things like numerical literals

(like 2 or 3.14), though. Just use int or double/float for that.

auto num1 = 3.14159; // * avoid this!

auto num2 = 4; // * and avoid this!

int num3 = 5; // * however, these are fine, since the

auto num4 = num3 + 5; // type is deduced from num3.

It's most useful when dealing with functions or structs, as they tend to involve long and complicated datatypes that can get annoying to write every time.

7.4: arrays

Arrays of data. Stores a bunch of values sequentially. You can create arrays of any datatype; ints, floats, structs, pointers, and even arrays.

// An array of 6 ints

int varlist[6] = {

2,4,6,8,10,12

};

Each value of an array is called an element. The act of getting a element from an array is called reading. Setting a value of an array is called writing, though it's sometimes also called assignment. Doing either of those two things to an array is also referred to as accessing.

To access a certain element of an array, you need to use <array>[<index>],

with <index> being the offset from the start of the array. This means

that array indices start at 0! If you wanted to access the element 2 from

varlist in the above example, you would use varlist[0], not varlist[1].

int varlist[6] = {

2,4,6,8,10,12

};

// you can assign members of an aray with =

varlist[0] = 777;

printf("varlist[0]: %d\n",varlist[0]); // prints 777

printf("varlist[3]: %d\n",varlist[3]); // prints 8

Arrays can also be created via empty brackets, in which case they will have their size be based on how many elements you initialized them with.

// this is the same as list[4], except you don't have to keep track of the

// amount of elements you added.

int list[] = {

30,40,50,60

};

Accessing data past the array's size will result in undefined behavior. If

your luck's good, the program will give you a nice "Segmentation fault" error.

Other times, it may crash silently, or even worse, not crash at all. Also, for

arrays, the last element is at the index [<size>-1], not [<size>]. This

means:

int list[4] = {

30,40,50,60

}

// INCORRECT! this should be changed to list[3], not list[4].

int last_elem = list[4];

Not initializing the array with any meaningful data will result in it being filled with garbage uninitialized data.

// this array will be filled with garbage, as it's uninitialized.

int unknown_data[60];

However, if you initialize the array using any braces, then all members that you don't explicitly set get reset to 0.

// even when you explicitly do set members of the array, the rest that haven't

// been set will get set to zero.

// because of this, this array will contain the data { 1,0,0,0,0 }.

int some_data[5] = { 1 };

// likewise, if you leave the braces empty, you will create an array that has

// every element set to 0.

// this array will be { 0,0,0,0,0 }.

int cleared_data[5] = {};

Setting specific members of an array during initialization is referred to as

designated initialization. This is done by using [<index>] = <value>

inside of the braces of the array.

// an array with only [3] and [1] being the only nonzero members

int bank[8] = {

[1] = 10,

[3] = 30

};

Just like as described earlier, when using braces for initialization, members

of an array that you don't set will get reset to zero. Because of this, the

array bank in the code block above will have every member except bank[1]

and bank[3] automatically set to 0.

When using array designated initialization without an array size specified, the size of array is dependent on where the farthest member is. So, with the following array:

int list[] = {

[0] = 30,

[8] = 9

};

it would have a size of 9 elements, with elements list[1] through list[7]

being set to zero.

You might also wonder at some point whether you can change an array's size after it's been created. The answer is no. You can, however, create arrays that use a variable for setting their initial size. These are referred to as variable-length arrays, or VLAs for short.

// normal array

float data1[40] = {}

// variable-length array

int size = 60;

int data2[size]; // NOTE! VLAs can only be initialized afterwards!

What happens if an array's size is 0, or negative? Undefined behavior, so probably a crash.

Multidimensional arrays are also a feature of C. Don't let the name make them

sound complex, it just means you can index them with multiple indices, like

arr[y][x]. An example:

int arr[3][3] = {

{3,5,4},

{6,7,8},

{9,10,11}

};

// prints the data at row 1, column 2 of the array (aka, 8)

printf("arr[1][2]: %d\n",arr[1][2]);

Multidimensional arrays like the above that have 2 different dimensions are referred to as 2D arrays. Likewise, arrays with 3 different dimensions are called 3D arrays.

A useful note about multidimensional arrays is that the first dimension can have an empty size, if you wish for it to automatically be deduced based on how much elements you put in the array. The below code would function the same as the code above:

// it's still a 3x3 array.

int arr[][3] = {

{3,5,4},

{6,7,8},

{9,10,11}

};

// this would also print 8.

printf("arr[1][2]: %d\n",arr[1][2]);

This syntax only works for the first dimension, though. arr[][3][4] is

valid, but not arr[3][][4], or arr[3][4][], or arr[][][3].

Multidimensional arrays can also be simulated by just creating an array with

the same area as it's multidimensional counterpart. For example, a 4 * 3

multidimensional array arr[3][4] (Y is first!) could also be seen as arr[3 * 4].

To index this multidimensional array, you would use arr[x + y * width], where

width is the height of the array, rather than arr[y][x]

#include <stdio.h>

#define MAP_SIZEX 4

#define MAP_SIZEY 3

const int map[MAP_SIZEX * MAP_SIZEY] = {

3,5,4,9,

6,7,8,12,

9,10,11,16

};

int map_get(int x,int y) {

return map[x + y * MAP_SIZEX];

}

int main() {

// this would print map[1][3] (aka, 12.)

printf("map(3,1): %d\n",map_get(3,1));

return 0;

}

It's incredibly common to see this syntax used in regards to 2D data structures, as there's actually many situations where 2D indexing is required, but utilizing C's actual multidimensional array syntax is impossible (usually due to the size of the array not being a known value at compile-time.)

7.5: sizeof & size_t

You can view the size of any data type or variable by using the sizeof()

operator. It'll tell you low long it is in bytes. Yes, it's an operator, not

a function, despite how it looks.

int variable = 5;

int varlist[6] = {

2,4,6,8,10,12

};

// sizeof returns a size_t, and size_t should use %zu, not %u.

printf("size of variable: %zu\n",sizeof(variable));

printf("size of varlist: %zu\n",sizeof(varlist));

Though the above sample looks fine from a glance, there's one important thing

to note: the type of data that sizeof returns is actually not a normal int,

but a size_t. It's a

somewhat-special type, with a size that depends on the system you are compiling

for. It's primarily meant to be used for variables that relate to sizes and

indexes, hence the name. Because of this, it's guaranteed to be the largest

possible integer type, usually 64 bits wide. It's preferred to use it

whenever's appropriate, as making a variable size_t makes it incredibly

obvious as to what you're using it for, while int can sometimes be seen as

vague.

To use size_t, you must include a header that has it, first. If you read

the link in the text above, you would notice that multiple headers actually

offer it. For me, personally, I include stdlib.h. When using size_t,

remember that it's still an integer, so you can do everything that integers can

do as well.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main() {

int varlist[] = { 2,4,6,8,10,12 };

size_t varlist_size = sizeof(varlist);

printf("varlist_size: %zu\n",varlist_size);

return 0;

}

7.6: stdint.h

char is 8 bits, short is 16 bits, int is 32 bits. That's the case...

usually. Sometimes int is 64 bits! Sometimes char is 16 bits! You can't

depend on data types always being the same size everywhere! However, there's a

way to get around this. If you want integers that are always a certain size,

either because you're targetting a certain platform, or if your data needs to

be guaranteed a specific size, you may use the stdint.h header. You can find

a complete list of types that the header offers you

here. As for the types that

I usually use:

// Include stdint.h to use the types.

#include <stdint.h>

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

// Signed (aka, numbers that can be negative) types:

int8_t num_a = -4;

int16_t num_b = -400;

int32_t num_c = -400000;

int64_t num_d = -4000000000000;

// Unsigned types (aka, numbers that are never negative):

uint8_t unum_a = 4;

uint16_t unum_b = 400;

uint32_t unum_c = 400000;

uint64_t unum_d = 4000000000000;

// These will always print the sizes 1, 2, 4, and 8 respectively.

printf("sizeof(num_a): %zu\n",sizeof(num_a));

printf("sizeof(num_b): %zu\n",sizeof(num_b));

printf("sizeof(num_c): %zu\n",sizeof(num_c));

printf("sizeof(num_d): %zu\n",sizeof(num_d));

// The same goes for these. They're the same size, just unsigned.

printf("sizeof(unum_a): %zu\n",sizeof(unum_a));

printf("sizeof(unum_b): %zu\n",sizeof(unum_b));

printf("sizeof(unum_c): %zu\n",sizeof(unum_c));

printf("sizeof(unum_d): %zu\n",sizeof(unum_d));

return 0;

}

The above fixed-width integer types are often shortened to alternate names:

- For unsigned types,

u8,u16,u32, andu64. - For signed types,

s8,s16,s32, ands64, or alternatively,i8,i16,i32, andi64. The Rust programming language actually uses the latter's naming scheme.

8: arithmetic

8.1: Basic operators

In C, you are given access to the basic +, -, *, /, and % operators,

for addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and remainder of a

division, respectively.

int n = 1;

n = n + 3; // n is now 4

n = n * 5; // n is now 20

n = n / 2; // n is now 10

n = n - 1; // n is now 9

n = n % 4; // n is now 1 (remainder of 9 / 4)

Additionally, you can use +=, -=, *=, /=, and %= to apply a math operation

to something and assign it immediately after. In other words:

int n = 1;

// this line...

n = n + 5;

// ...does the same as this line!

n += 5;

Along with the above, there are special operators for incrementing & decrementing values.

-

x++andx--will increment after the expression. that is, after the next semicolon of your code. -

++xand--xwill increment before the expression. that is, before the block even starts.

int a1 = 4;

int b1 = 4;

// a2 would become 4, as it takes the value of a1 before incrementing.

// b2 would become 5 instead, as it takes the value of b1 *after* incrementing.

int a2 = a1++;

int b2 = ++b1;

// Both still increment regardless, though, so a1 and b1 would both be 5 by

// the time this line down here is reached.

8.2: Bitwise operators

Before I describe how bitwise operators work, I have to explain what an integer is on your computer. I glossed over it, though in order to understand bitwise operators, you have to know.

Say you had the number 53. This is a base-10 number. It's what society

usually counts things in. Base-10 means that each digit can be one of 10

things, before the next digit gets increased. A base-10 digit will go through

0,1,2,3,4, 5,6,7,8,9, and then the next digit increases, while the current

digit gets set back to 0. Base-10 numbers are also often called decimals

(because 10 == Deca). Yeah, it's confusing, since it's also very common for

people to call the little dot next to a number a decimal.

Now, say you had the number 0x13 (aka, 19 in decimal). When using the prefix

0x, this means we are using a base-16 number, often referred to as a

hexadecimal number (because 16 == Hexa). Because it's base-16, each digit

will be one of 16 things: 0,1,2,3, 4,5,6,7, 8,9,A,B, C,D,E,F, before

carrying to the next digit. Digits of hexadecimal numbers are referred to as

nybbles.

0x0A in hexadecimal would equal to 10 in decimal. 0x0C would equal to

12. 0x10 would equal to 16. 0x40 is 64. 0x100 is 256. 0xFFFF is

65535. You get the idea by now.

However, the other most important base to know is base-2, commonly referred to

as binary. Binary numbers are often prefixed by 0b, though it's not rare to

see them have no prefix at all. Now, just as you learned with the other two

bases, base-2 means a digit can only be one of 2 things. In this case, it's 0

(referred to as cleared) or 1 (referred to as set). Binary digits are

also called bits.

Now, if we wanted to calculate 1 + 1 in binary:

1

+ 1

----

= 10 (AKA, 2 in decimal.)

Just like how a decimal number would carry after a digit goes over 9, a binary

number would carry after a digit goes over 1, so 1 + 1 would equal to 0b10.

Likewise, with 2 + 7, or 0b10 + 0b111:

111

+ 10

-----

1001 (AKA, 9 in decimal.)

Besides binary, decimal, and hexadecimal, there's other bases such as base-8, though they're not used very much.

Also, as an aside, bits go from right to left, not left to right! The

number 0b0010 would equal to 2, NOT 4. The two zeroes to the left are just

there for padding, the same way that the number 003129 is just the same as

3129 but with zeroes added at the start.

When people think of binary, they often think of them as going from left to

right, though you have to remove this notion from your mind entirely once you

start programming with binary numbers.

For computers, all numbers are internally calculated using binary. Each number

also usually takes a set amount of bits in size: usually 8, 16, 32, or

64. Along with this, almost all of the memory on your computer is separated

into 8-bit chunks, called bytes.

For ease of reading, larger binary numbers would often be written with :

inserted inbetween every byte (or sometimes, every two bytes).

0b00000001111101001111011000111110 (32831038) would become

0b00000001:11110100:11110110:00111110. Note that this isn't a feature of any

programming language, but more of a notation thing. A similar notation also

exists for hexadecimal: 0x04000000 is sometimes written as 0x0400:0000.

It's the same principle as how larger decimal numbers are usually written with

commas to separate them, like how you usually see people write 1,000,000

instead of 1000000.

An important aspect about binary is knowing the terminology for what each of

your bits. The least-significant bit, or LSB for short, is the

far-rightmost digit of the number. For example, 0b10000000 (128) would have

an LSB of 0, as the far-rightmost digit is 0. The MSB, or

most-significant bit, is the far-leftmost bit of the number. 0b10000000

would have an MSB of 1, since the far-leftmost bit is 1. A bit being farther to

the right or farther to the left is also referred to as the bit being lower or

higher, respectively.

Bits are also numbered, depending on how far to the right they are, with the

LSB being bit 0. For instance, the 8-bit number 0b01110101 (117) would have

the numbering:

0 | Bit 7 (the MSB)

1 | Bit 6

1 | Bit 5

1 | Bit 4

0 | Bit 3

1 | Bit 2

0 | Bit 1

1 | Bit 0 (the LSB)

Each bit having an index is very useful, as it means you can calculate what a

binary number is in decimal by just checking whether or not each bit is set.

0b01110101 can be seen as (2^6)+(2^5)+(2^4)+(2^2)+(2^0) (you don't include

the cleared bits), or 64+32+16+4+1, resulting in 117.

So, how are negative numbers done in binary, then? I've described them a few times briefly, but i'll explain in full now. Integers that can be either negative or positive are referred to as signed integers, and the way they work is that rather than using all of their bits as a full, unsigned number (i.e 0b11111111 being 255), the MSB is used to indicate whether or not the number is positive (0), or negative (1). Because the MSB now has this property, it is also referred to as the sign bit when dealing with signed numbers. In addition, the inversion of the bits before the sign bit (plus one) is treated as the magnitude.

..now, what does that mean? Say you have an signed 8-bit integer in binary,

0b11111000. You want to represent it as a decimal instead. The steps are as

follows:

- The number is

0b11111000. the sign bit is 1, so this is negative. - Since it's negative...

- Invert the bits after the sign bit to get

0b0000111, then add 1 to get the value it's supposed to be. In other words,0b0001000, or8. - Since the sign bit was set, we make our result negative, so

-8.

- Invert the bits after the sign bit to get

The s8 0b11111000 is -8. Simpler than it sounds, isn't it? Another example,

with the number 0b11000101:

- Sign bit is 1, so it's negative.

- Since it's negative...

- Invert bits after the sign bit to get

0b0111010. Add 1 to get0b0111011, or59. - Sign bit was set, so we make the result negative, giving us

-59.

- Invert bits after the sign bit to get

As for 0b10000000:

- Sign bit is 1, so negative.

- since it's negative...

- invert bits after the sign bit to get

0b1111111. add 1 for0b10000000, or128. - sign bit was set, so our result is

-128.

- invert bits after the sign bit to get

If you have a keen eye, you might have noticed that since the lower bits are

treated as the magnitude, this means that signed integers have their maximum

value shaved in half. A u8 can go from 0 to 255, while an s8 can go from

-128 to 127 (not 128!).

The bitwise operators are operators designed to work with numbers' bits

directly, for tasks that involve setting & manipulating specific bits of a

number. C includes the operators |, &, ^, <<,>>, and ~ for use with

bitwise operations.

Before I explain each, here is an example of all of them in use. (save for ~, for

reasons that will be explained further)

// n is 12.

int n = 0b1100;

n |= 1;

n ^= 1;

n <<= 2;

n &= 0b10000;

n >>= 3;

// now, the above will:

// 1. combine the bits of n with 1 (1100 | 0001 == 1101)

// 2. flip the bits of n using 1 (1101 ^ 0001 == 1100)

// 3. shift n's bits to the LEFT by 2 bits (1100 << 2 == 110000)

// 4. mask n's bits with the number 0b10000 (110000 & 010000 == 010000)

// 5. shift n's bits to the RIGHT by 3 bits (010000 >> 3 == 010)

// resulting in 10 in binary, aka, 2.

Explanations for all of the operators in the above example will be shown below.

Bitwise OR is done using the | (not to be confused with ||!) operator.

It returns 1 if either bit is 1. Could also be seen as "merging" the two bits.

Now, you might be asking how the diagram above applies to numbers that have multiple bits. In that case, you simply apply the operation to each of the two operands' bits. For instance, for a bitwise OR, the result's bit 0 would be the first number's bit 0 OR'd with the second number's bit 0, then the result's bit 1 would be the first number's bit 1 OR'd with the second number's bit 1.... and so on, for every bit. This also applies to every other bitwise operator in this chapter!!! Remember it, otherwise you may get confused.

To illustrate, 0b0011 | 0b1110 would be calculated as:

- Bit

0is1 | 0, so it'd be1. - Bit

1is1 | 1, so it'd be1. - Bit

2is0 | 1, so it'd be1. - Bit

3is0 | 1, so it'd be1.

...resulting in an answer of 0b1111. Additional examples:

0b1001 | 0b0100would result in0b1101.0b0000 | 0b1110would result in0b1110. Obviously, ORing a number with 0 would just result in said number not changing.

Bitwise AND is done using the & (not to be confused with &&!) operator. It

only returns 1 if both bits are 1.

For example:

0b1001 & 0b0100would result in0, as they have no corresponding bits.0b1101 & 0b1100would result in0b1100, as bits 3 and bits 2 for both numbers are set.

You can use number & 1 to check whether or not an integer is odd or even; if

number is odd, this operation will return 1, if number is even, this

operation will return 0. In fact, many languages (including C) optimize

calculations of number % 2 with number & 1 under the hood, along with other

similar divisions.

Bitwise XOR is done using the ^ operator. It inverts the bits of the

first number, if the corresponding bits in the second number are set. Also,

before you ask, yes, it's ^. This means that doing 2^3 in C would equal to

1, not 8, as there is no exponential operator in C.

For example:

0b11 ^ 0b01would result in0b10.0b11 ^ 0b10would result in0b01.0b1001 ^ 0b0100would result in0b11010b1101 ^ 0b1100would result in0b0001.

For most processors, integer addition is calculated as a long series of XORs

and ANDs for each bit. Oh, and if you're wondering why C uses the ^ operator

for XOR and not exponents, it's because CPUs having such a function wasn't very

common at all when C was first designed.

Bitwise left shift is done via the << operator. It shifts all the bits of

a number to the left, by the amount of bits that you specify. It's used via the

syntax x<<shift, where shift is the amount of bits to shift x left by.

For example:

0b1100 << 2would result in0b110000. Notice how zeroes fill the empty bits to the right.0b1101 << 3would result in0b1101000.